Welcome to Bradgile.com! This is a beta version of the site as it decides what it wants to be when it grows up. For now, it is an informational resource composed by Brad Nelson around "Agile" with a capital "A." The information here is a culmination of Brad's experience and studies in Agile Software Development (XP, Scrum, Nexus, SAFe, LeSS, Kanban, Lean, Modern Agile, and DevOps), Product Management, and User Experience. New content will be added, in no particular cadence, and current content is apt to change (as it already has). Also feel free to checkout my articles on LinkedIn for more free information. Thank you for stopping by and please reach out to me via the provided contact and social media links with any questions.

The Agile Mindset

In 1941, Konrad Zuse, a civil engineer, created the first functional and programmable computer. For decades, engineers would continue to evolve computer science through iterative and incremental innovation. However, by the turn of the century most companies had adopted technology, and with this new demand came a more rigid and stagnant approach to software development — one steeped in process and bureaucracy. In response, industry leaders gathered in 2001 and published the Agile Manifesto for Software Development. This declaration, grounded in four values and twelve principles, challenged the prevailing mindset and became a symbolic rallying point for a more human-centric, adaptive way of working.

A manifesto is a public declaration of beliefs, and the Agile Manifesto is exactly that. It is not a process but a mindset: a way of thinking and acting that centers on people and culture. Rooted in Lean Principles, its focus is to deliver value as defined by the customer and to continuously improve the ability to deliver that value by eliminating waste and relentlessly learning. By working iteratively and incrementally, empowered cross-functional teams can optimize the flow of value, validating solutions as they go while reducing work that adds no real benefit. In the end, Agile is less about rigid practices and more about cultivating adaptability, collaboration, and learning as the foundation of lasting success.

Empiricism

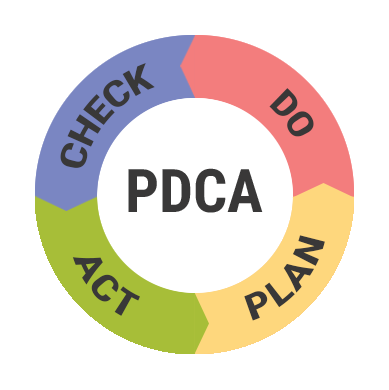

Agile and Lean are founded on empirical process control, or empiricism. Empiricism is the theory that the only knowledge humans can possess is based on experience, with an emphasis on evidence. It is a fundamental part of the scientific method, the core building block of all natural sciences. The scientific method is a process of validating all hypotheses by observation, and is represented as the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle (often referred to as Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) in Lean). This means that, although a person may come with professional experience and knowledge, empiricists understand that every company, product, and situation is unique, and therefore will not be satisfied until results can be verified. Through empiricism, agilists know that the most effective way to validate, learn, and innovate is through experimentation with proper attention to the process.

Empiricism requires an emphasis on and diligence around transparency. In order to effectively inspect and adapt processes, tools, products, etc. there needs to be clear and easy access to all available knowledge in relation to the subject of inspection. This is essential, and necessitates disciplined organizational skills, effective communication, emotional maturity and psychological safety. Likewise, transparency, inspection and adaptation are key to identifying and eliminating processes that the customer does not want to pay for &emdash; better known as “waste.”

Empiricism requires an emphasis on and diligence around transparency. In order to effectively inspect and adapt processes, tools, products, etc. there needs to be clear and easy access to all available knowledge in relation to the subject of inspection. This is essential, and necessitates disciplined organizational skills, effective communication, emotional maturity and psychological safety. Likewise, transparency, inspection and adaptation are key to identifying and eliminating processes that the customer does not want to pay for &emdash; better known as “waste.”

The Three Ways

The easiest way to remember and implement the Agile mindset is by following the “Three Ways.” The Three Ways are the values and philosophies that frame the processes, procedures, and practices of DevOps, as defined by Gene Kim, Kevin Behr, and George Spafford in The Phoenix Project. They are as follows:

- The First Way: Fast Flow emphasizes the performance of the entire system to deliver customer value as quickly and frequently as possible, as opposed to the performance of a specific individual, department, or work.

- The Second Way: Feedback Loops is about shortening how long it takes and amplifying the ability to receive feedback so necessary corrections can be made as needed to improve quality and sustain the fast flow of value.

- The Third Way: Continuous Improvement is about creating a culture dedicated to improving by understanding that learning comes from experimentation, risks, and failures, while mastery is achieved from repetition and practice.

The Eight Wastes of Software Development

Waste: a process that a customer does not want to pay for.

In Lean, the wastes (often called muda) are activities that consume resources but don’t add value for the customer. While the practice of eliminating waste dates back to the Ford assembly line, it was Taiichi Ohno, father of the Toyota Production System (TPS), who first identified seven distinct forms of waste. An eighth was later added by Lean practitioners. These eight wastes are often organized under the acronym DOWNTIME as a mnemonic device and have been translated into software development as follows:*

- Defects (Unplanned Work): Unplanned work is the silent killer of IT. It shows up as incidents, outages, failed changes, hotfixes, patches, or security incidents—anything outside of the estimated work for a project, product, or feature. Unplanned work inflates WIP, drives context switching, and creates delays. The first step is to track it. From there, teams can reduce it with test-first practices, built-in quality, and refactoring as you go. DevOps automation for testing and deployment further shortens delivery time, gives immediate feedback, and removes the risk of human error.

- Overproduction (Extra Features): A large percentage of software features go unused or add little value. Yet every extra feature consumes resources: hosting, bug fixes, regression testing, and maintenance. Monitoring usage helps teams improve or retire unused features. A minimum viable product (MVP) approach reduces the chance of waste reaching production. Product thinking, research, and low-investment validation techniques increase the odds of building the right thing the first time, while maximizing the value realized.

- Waiting: Waiting happens any time progress is blocked by dependencies, approvals, or environments. Developers often start new work while waiting, which causes context switching and reduces focus. When the blocked work resumes, context is lost and mistakes are more likely. Agile teams limit WIP and shorten feedback loops to reduce waiting. Practices like continuous integration, smaller work items, automation, and frequent releases validate value sooner and reduce the risk of code becoming obsolete or broken by other changes.

- Non-Utilized Talent: While not an original Muda as defined by Ohno, one of the biggest wastes is failing to use the creativity and expertise of the people closest to the work. Too often, decisions are centralized, leaving employees disengaged and ideas unheard. Agility shifts leadership from command-and-control to servant leadership, creating safety for people to share their insights. When individuals are empowered with clarity of vision, they’re motivated by autonomy, mastery, and purpose. Engaged employees deliver higher productivity and retention, which increases profitability and reduces cost.

- Transportation (Handoffs): The more people who touch a work item, the more expensive it becomes. Handoffs create delays, misunderstandings, and rework. Reducing handoffs means optimizing the value stream and team workflow. Smaller, cross-functional teams bring all the skills needed to complete the work together at the start, reducing cycle time and dependency on others. Automation and standardized work also reduce unnecessary handoffs by eliminating repeatable steps and minimizing the need for specialized intervention. Likewise, empowering teams to decide locally reduces the delays caused by passing decisions up and down the chain.

- Inventory (Over-Planning & Incomplete Work): A software team’s inventory is its work items. Whether gathering too many requirements too soon or failing to complete what was started, both forms of inventory lock up effort without delivering value. In Agile, there is no “partially done.” Work is either done or it is work in process (WIP). Every unfinished item ties up time, effort, and resources with no return, while excessive WIP delays delivery, increases defects, and reduces quality as developers lose focus. On the other side, stockpiling requirements or speculative designs is equally wasteful, since reality inevitably changes and those plans often end up discarded. Agile and Kanban remind us to limit WIP, slice work into smaller deliverables, and plan just-in-time. This ensures earlier feedback, reduces rework, and prevents teams from drowning in a backlog of incomplete or outdated work.

- Motion: Motion really stands for unnecessary motion, whether mental or manual movement: task switching, relearning the same lessons, or performing the same manual steps again and again. It drains focus, delays delivery, and invites errors. Teams combat this by building a culture of knowledge sharing (pair programming, demos, communities of practice) and by creating reusable assets like templates, libraries, and design patterns. Automation eliminates repetitive manual work and reduces the possibility of human error while freeing people to focus on higher-value problems.

- Extra Processing (Over-Engineering): Over-engineering is the trap of building overly complex systems, abstractions, or architectures for needs that don’t exist yet. It might be gold-plating code, designing for infinite scale, or over-abstracting for imagined future use cases. Over-engineering adds cost, slows down teams, and increases fragility without delivering customer value. Agile combats this with the principle of YAGNI (“You Aren’t Gonna Need It”), simplicity, and focusing on delivering the smallest thing that works today.

*This is my translation. There have been other translations such as the one found in the 2003 book "Lean Software Development: An Agile Toolkit" by the Poppendiecks.

Measure What Matters

As Lord Kelvin famously quoted, “If you can not measure it, you can not improve it,” metrics are the measurement of data related to the work. Examples of this might be how many items were completed in a given time period, how long it took an item to make its way from “aha” to “ka-ching,” and how many defects were reported. Perception often doesn’t match reality and metrics help us create transparency to areas of improvement or progress towards an improvement or deliverable. Oftentimes a snapshot of data is not the most useful, but tracking data lineage allows the ability to see trends and patterns. It also allows us to know when we've achieved our goals. As empiricism is the belief that knowledge is attained through observation, metrics are a source of observation in which we can attain knowledge. The most important thing to remember when collecting data is our inherent biases and the specific purpose for which metric is used.

Visualize Your Work

One of the top tools for creating transparency, communication, and organization is the ability to visually represent the work, ideas, and concepts. "A picture is worth a thousand words" and when dealing with the complexity of software development finding ways to visualize information can be crucial to a shared understanding (and sanity). This is commonly implemented through mapping (value stream, impact, story, etc.), visual boards, and radiators. Mapping tends to be a tool for ideation and refinement, whereas visual boards are typically used to display workflows, the work itself, and any related information. Radiators are used to radiate information, especially those attained by metrics, and may be comprised of tables, charts, and graphs.

Software Craftsmanship

Do you want the brand new iPhone or a brick phone from the 80s? Think of all of the advancements that went into being able to produce the hardware to run your software, from man's beginning of sharpening sticks, to shaping rocks, to smelting metal ore, so on and so forth. As new ways of doing things unlocked more advanced technology for humankind, so has modern development practices for software. Software craftsmanship emphasizes coding as a craft and therefore expects developers to not only create working software, but also well-crafted software. Developers are expected to hone their craft by challenging the way things have always been done and experimenting with new techniques.

Go To The Work

The best insights emerge when leaders step away from dashboards and go directly to the source. This is a guiding principle that Toyota calls Gemba, or “the real place.” In software, this means walking the board with your team, observing work in action, or talking directly with users and stakeholders. A true Gemba walk isn’t about handing down criticism, it’s about asking questions, showing respect, and uncovering hidden inefficiencies that only become visible when you’re present. Whether it’s managers observing a daily huddle, product leaders shadowing user workflows, or teams visiting a customer’s real environment, these moments of presence build deeper understanding and unlock the improvements that matter most.